Barcelona-based developer Altered Matter has been working on its physics puzzler Etherborn for several years now. It’s a game built around the concepts of finding truth in the unknown while working through vast, multi-stage puzzles and defying gravity in the process.

If those two mechanics sound rather different from each other, that’s because they are, and it’s a split that stays with the game throughout. That split isn’t necessarily to Etherborn‘s benefit, though there’s still enough for patient puzzle fans and 3D thinkers to enjoy here.

Into the Ether

Normally, you wouldn’t expect to read much about a physics puzzler’s story, but Etherborn tries to be a bit different in that regard. All the running up walls and piecing stages together is loosely based on an equally loose story about an enigmatic being’s search for truth.

What truth? Well, that depends.

The being, a cluster of nerves forming a tree in the chest and brain, apparently has an emptiness that must be filled, though it isn’t aware of the emptiness and doesn’t know what fills it. So, like you do, it starts listening to a geometrically abstract, pulsing, golden Thing that talks philosophy and promises to reveal all the unknown that needs to be known.

As you progress through each stage, that changes to the Thing telling you about the nature of the universe and how humans came to try and dominate it. Eventually, that turns into how people lost their relationship with — and place in — nature by turning to language, using it to name and dominate creation whilst simultaneously rejecting all other paths in the process.

The existential bits don’t get developed fully enough to contain real meaning before Thing switches gears to something akin to an environmental message, which also isn’t fully developed.

Moreover, it’s all a little confusing. That’s not because it’s a deep, philosophical message on the nature of humanity. No, there isn’t anything here that hasn’t been said before, and with more impact.

It’s because each message is wrapped up in convoluted writing, writing seemingly designed to suggest the profound by straying into purple prose, when something more direct could convey meaning better.

Or: Humans feared what they didn’t understand and tried controlling it through limiting the unknown.

And that’s every scene with narration.

Those who want to engage in the message on offer here will find it doesn’t work with this style of game anyway. The being’s goal is to navigate through each stage by putting things in order. Chaos gets tamed through the player imposing their will on creation, manipulating it to their own desires for a goal they aren’t even fully aware of — the exact behavior the game tries telling you led humanity astray in the non-gameplay portions.

Were there some big payoff with insight into the human condition that isn’t already commonplace in contemporary media, these narrative issues might be easier to overlook. As it is, conversations with Thing are just where you stop paying attention until the scene changes again.

Fortunately, you don’t really miss anything if you do stop paying attention. These segments end each stage, while opening up new segments on the giant tree you travel up and around on your journey towards…whatever it is (or isn’t).

In other words, the narrative has little to no bearing on the actual gameplay. Whether that’s good or bad depends on your perspective, since it makes dealing with the annoyances and gaps in logic easier. However, it also begs the question of why bother building a puzzle game around this kind of plot when the plot doesn’t even matter.

Climbing the Walls

All this probably makes it sound like Etherborn is a mess. Well, it isn’t.

The puzzle design is consistently brilliant. When you hear “physics puzzler,” you might think something like Human Fall Flat or something similar. Etherborn is more like Super Mario Galaxy, only gravity will kill you as often as it’s your friend.

The goal in each stage or stage segment — since some levels are divided into multiple areas — is, obviously, make it to the end. To do that, your character will need to collect shining, faceted, sphere-like objects and place them in specific areas to impact some aspect of the immediate area.

That sounds simple, but Etherborn quickly ramps things up by giving you multiple options of where spheres could go and only a few to work with.

It translates to working out the correct order for progression, which ends up being as much a part of the puzzle as the actual jumping, climbing around, and so on.

At times, it’s rather intricate as well. Some parts have multiple steps required to finally reach a sphere you need to activate another area, which has its own puzzles and finally leads you to the stage’s end.

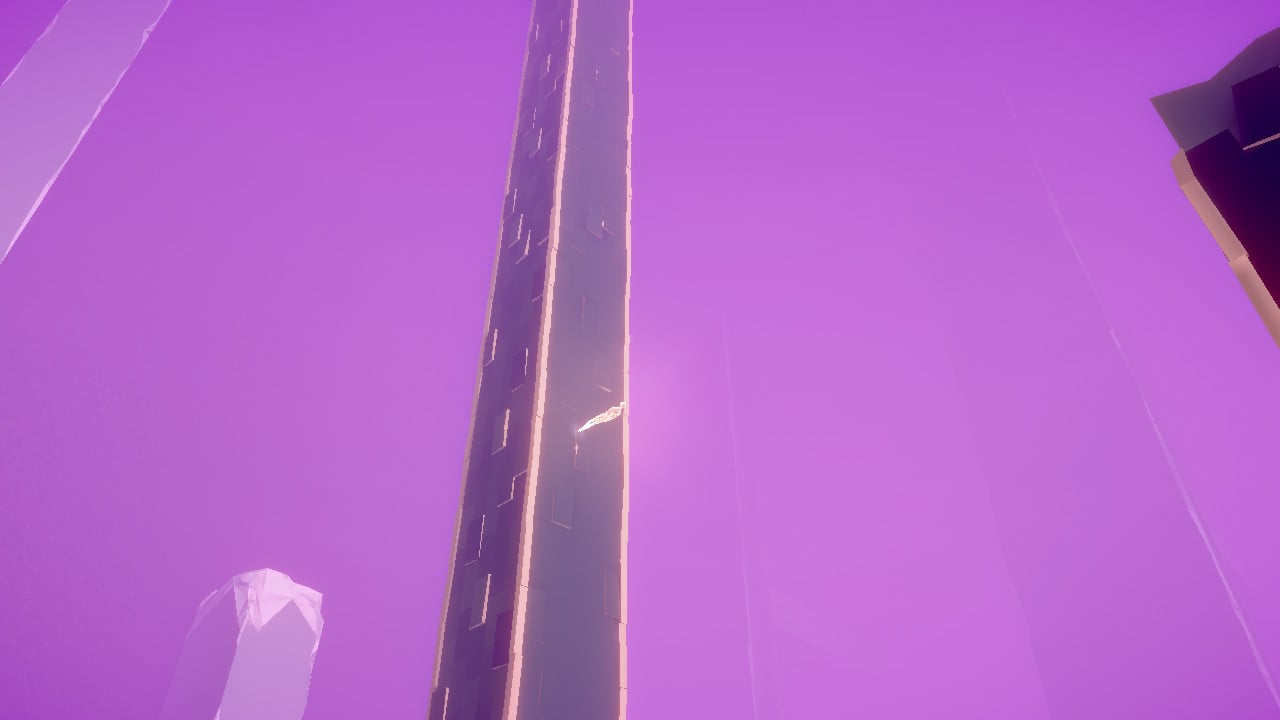

Your character doesn’t just walk around on the regular floor to get to each area, though. In fact, depending on perspective, there isn’t a regular floor at all.

The game’s central feature is letting you walk up walls and around stage segments, with the physics changing depending on what surface you’re on. For example, jumping might take you “up” when you’re walking around normally. Run up a ramp onto the wall, and jumping takes you sideways.

Should you jump without a surface to land on, gravity takes hold. It can be the only way to reach that next area — or it can send you smashing against some barrier.

Keeping your footing and using gravity to your advantage fast becomes the game’s chief challenge, especially since the being can’t survive long drops. Fortunately, the game lets you start back where you fell, so there’s really no harm in failing again and again.

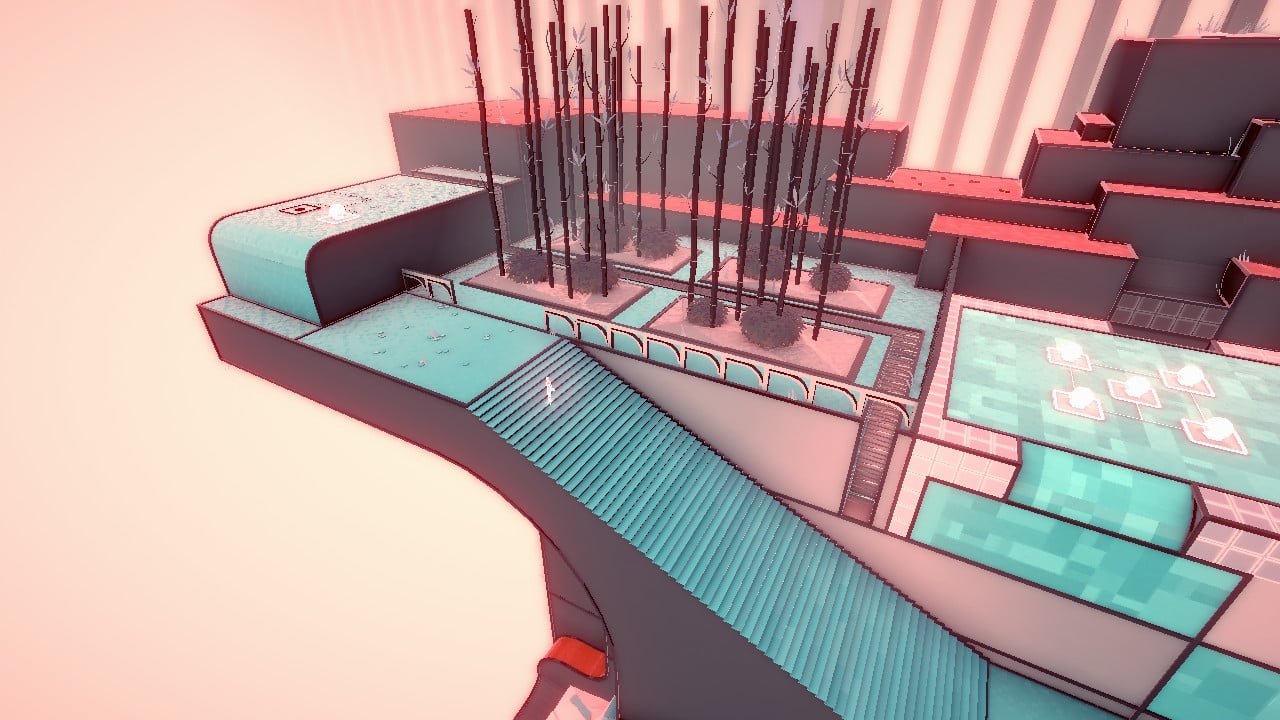

That tiny thing in the vast emptiness of space? That’s you.

The whole thing is a creative exercise in 3D thinking, as you try to work out which angle you need to approach a given situation from. There are plenty of moments where you find yourself wandering, having tried countless ways of reaching a certain point, when you make a random jump onto a nearby wall or platform that opens up a completely new segment of the stage. It’s a good feeling and indicative of the game’s clever design.

It should be a given by now, but Breath of the Wild this is not. Each puzzle has a specific solution you must work out, with no grey areas. (And yes, it’s ironic that a game cautioning against black-and white-approaches to existence uses a very strict black-and-white approach to design.)

Etherborn doesn’t let you cheat either. Obtaining a sphere by free-falling doesn’t count, so you have to plan all your movements with care.

Falling Down Again

The scope of each stage and that strict level design do come with a few flaws, though. Many stages and areas seem a bit bigger than necessary. They look great, and there’s a definite atmosphere for each. Yet it’s a huge pain — and inconvenience — to navigate these massive areas time and again while you’re figuring out how each stage works.

The being’s movements don’t always help alleviate this particular issue either. The walking pace is glacial, and though running does improve things a bit, it’s still not enough to make for quick traversal of each large area.

It might not sound like a huge issue, but so much repeated movement and backtracking to finish a stage means there’s little incentive to hurry on to the next one. Etherborn isn’t a game meant for marathon play sessions, except for the very patient.

Turning sometimes contributes to this issue. Your movements are rather on the wide side, meaning there’s no such thing as a sharp turn in Etherborn. The game’s insta-try-again feature keeps it from being too punishing, but it’s still annoying to fall off a ledge on accident because changing directions requires a wide swing.

There were a few points where the character clipped through solid objects and fell to its demise. There were also some areas the game had difficulty dealing with movement, mostly around the specific spots where you can transition from one surface to another.

Similarly, some platforms behave a bit oddly from time to time. One major feature of many puzzles is platforms that extend out when you approach them, blocking your way from one angle, but potentially acting as a path from another.

The issue is how the game recognizes when they should extend. For the most part, it works as it should. There are times when a platform that should extend, based on your proximity to it, won’t. Whether that’s by design because it’s not how the maker wants you to solve a puzzle isn’t certain, but there’s no apparent pattern to which ones won’t move unless you approach from the right angle.

Look, But Don’t Listen

There’s no denying Etherborn‘s visual style is striking, skillfully employing a minimalist approach that still manages to create mood. A big part of that is the color scheme, with each stage standing out as much for its visual identity as its puzzles.

The game’s soundscape is a bit less inspiring. Most of the tracks are very short, so you’re going to hear them a lot as you work through each stage. That’s fine for some tracks, but others are discordant or have an easily identifiable loop point that means it’s time to reach for the volume button.

—

The Verdict

Pros:

- Excellent puzzle design

- Clever use of visual elements

Cons:

- Overly convoluted, and inessential, narrative elements

- Stage scale and character movement don’t complement puzzles

Etherborn is one of those games that defies easy scoring. From the number and the negatives, you’d be forgiven for thinking this is game you should run away from. But if you’re a puzzle fan, enjoy thinking in 3D or just want to try something new and have a good bit of patience, it’s worth checking out.

[Note: A digital copy of Etherborn was provided by Altered Matter for this review.]

Published: Jul 16, 2019 10:43 am