Contrary to the title, the Four Horsemen really isn’t about the harbingers of the apocalypse. Rather, it is a visual novel/SLG (simulated life game) about a group of four immigrants/refugees growing up in a country that hates them and wishes they’d go back to where they came from. Since your country of origin is chosen at the start of the game, the game is more about the refugee experience and less about a particular people’s experience.

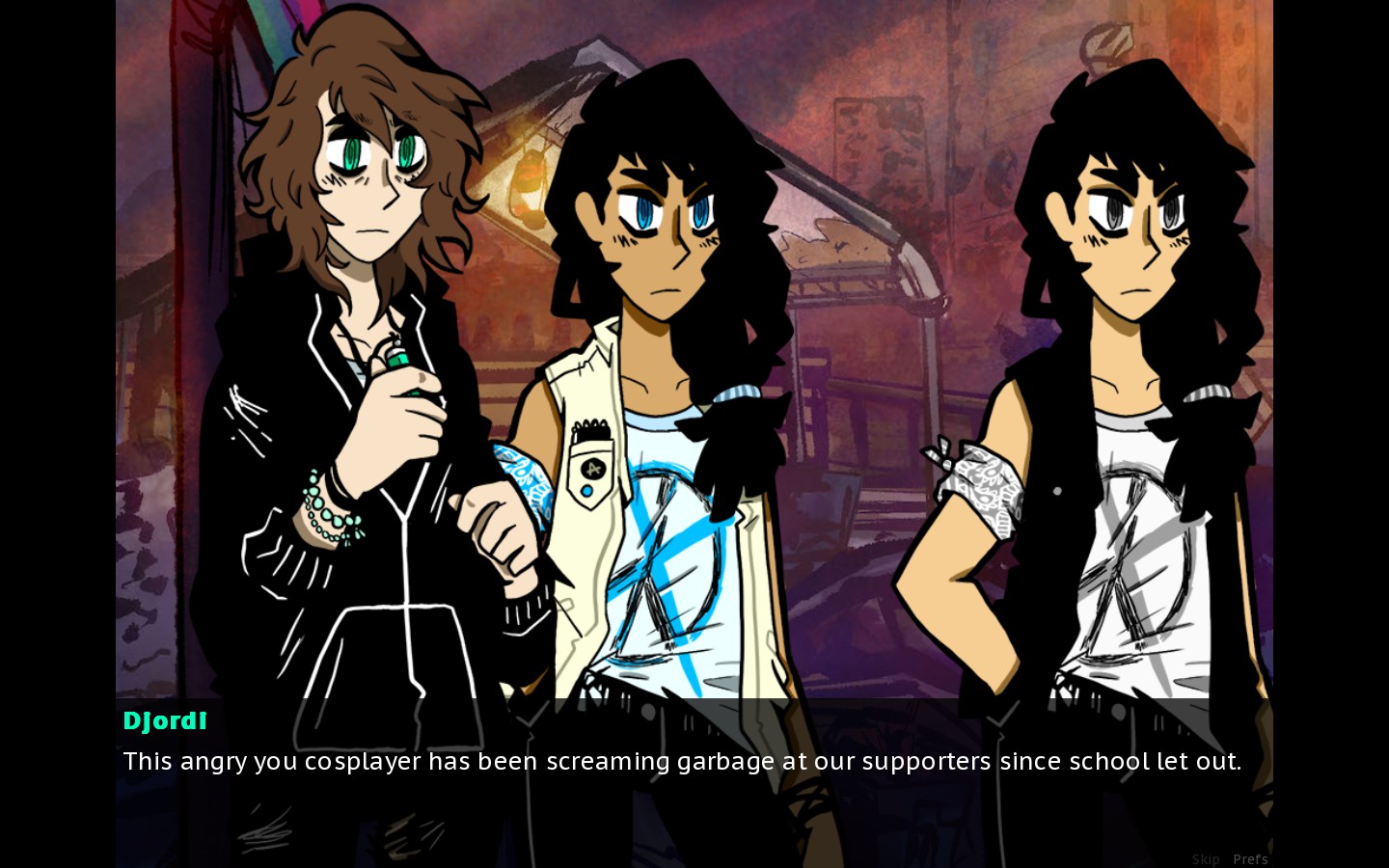

From Left to Right: War, Death, Famine, and Pestilence

The game starts with the four horsemen finding, claiming, and naming an abandoned WWII machine gun bunker, which, during the game, you slowly build up by having each character contribute to it in their own way. This is largely done by employing Death, a budding engineer, to craft new, ragtag inventions from items that characters find.

Everyone else feeds into this loop with the tasks they’re able to perform during the day. Pestilence can pillage a junk heap, Famine can work at a local store, War purchases items from the store at which Famine works. It doesn’t really make sense, sure, but nevertheless, it makes the base your own personal living space, adding to the overall experience reinforced by the overarching narrative.

The characters also populate the scene, displaying their

own interactions. Sadly this is usually obstructed by UI.

Four Horsemen‘s story largely plays out in this bunker. Centering on the refugee and immigrant experience, Four Horsemen tells a story that’s compelling and empathetic without preaching or pandering. Placing you into situations that are inspired by real-life immigrant experiences makes it feel alive.

I felt the hatred of my classmates and teacher when they referred to me as “the enemy”. I felt the implicit distrust that exuded from my boss and patrons at my after-school job. And any and every interaction with law enforcement became instantly tenuous.

Perhaps the greatest strength of the game is that it never makes you feel like you are being spoonfed simple answers. Every immigrant, whether it be one of the horsemen or one of their relatives, has their own ideas about how to handle their specific situation. When interacting with parents, you are usually offered solutions like,”Be quiet, don’t rock the boat,” or,”You say what you need to in order to survive.” These characters were jaded by what they’d experienced, both during wartime in their native land and now in their new “home”. Their words and ideologies speak volumes about who they are (were) as people and that, in turn, speaks volumes about the quality of writing in Four Horsemen.

On the other hand, the four main characters are young and have more fight left in them. War wants to stand up and fight for their rights. Death feels pressured to make something of herself because she’s a talented engineer and her people need a beacon of hope. Famine feels conflicted about his position in society. (He is mixed race and can sort of fit in with the natives, but he also feels a strong bond with his immigrant roots.) And Pestilence feels somewhat indebted while also feeling abused — he loves the country he has grown up in even though it hates him. The way these different perspectives work together and play off of one another is easily my favorite part of the game.

In turn, the believable characters lend credence to the situations in which they are placed; they even moor some of the more fantastical story beats. This creates a narrative loop where the characters are built up by the situations they endure and the situations are given life because you get to see the interactions of these characters — which feel much more real than you might at first think.

The story is also adequately supported by the game’s art and music. While there’s nothing particularly fancy going on here, the anime-inspired character designs get the job done (Although I could do without Famine constantly staring into my soul with his dead eyes!) and the backgrounds adequately accommodate the limitations of the character sprites. I do wish I had a better feel for the layout of the bunker and its surroundings, however, as I would hear the characters mentioning digging a latrine or the bunker’s isolated position and I’d never have a frame of reference.

The music can be off-putting at times, but it always felt like it supported the intended emotions of the scene. Whether it was a hard rock or acoustic song that played while you tried to talk your way out of being mugged while waiting for the bus or a somber piano piece as you reflected back on the moments leading to your escape from a war torn home, it always felt like it packed a punch.

As mentioned earler, you choose which country you want your characters to originate from. Personally, this is a decision I am split on. The strength of this approach is that you can see the same situation play out no matter which country is in power. You realize this could happen anywhere; that at any given time you are just a war away from becoming a refugee yourself.

That being said, the whole thing could come off as coldly systematic. Changing your country only changes a few lines of dialogue, your skin tone and hair color, your particular curse words (vernacular) and pronouns for things like mom and dad, and culturally relevant items, like drugs and food. But I never noticed deeply held cultural beliefs, religions, holidays, etc. truly embraced as a part of each culture’s unique heritage. This made it hard to feel grounded in any one particular culture.

Encountering versions of yourself from rival countries makes you realize that you might not be the good guy if you had power.

However, sometimes the game contradicts itself. Behind closed doors, the horsemen lament that Famine can pass as one of the natives, but when you are actually playing as Famine — particularly at his day job — you are constantly treated like a dog. Moreover, the game alludes to certain things that never actually build up.

In the picture of the clubhouse from above, you can see War and Pestilence close together, obviously flirting. But I never saw any real mention of this within the core dialogue (maybe I missed something?). Moreover, Famine is accused of just trying to get into girls’ pants — including Death’s — on numerous occasions. While he never denies this, there wasn’t any time that I saw him even so much as mention that a girl was hot.

These sorts of moments could cause some dissonance in what was otherwise exceptional characterization and dialogue.

The horsemen talk like real teenagers. I found this

very endearing, but some people won’t.

Perhaps my biggest problem with this game, though, was its multiple endings. There are nine endings with four main storylines. However, the stories often run concurrent to one another and as such, you can be forced to restart the game once you have completed one storyline. Concurrent storylines also often mean that character growth is limited to the storyline in which it happened.

This also lends itself to a lot of other problems. The game’s core loop of finding/buying supplies and crafting things is intentionally slow because it represents how hard it is to actually get things when you are a teenager — particularly a refugee teenager — that no one wants to hire, much more pay well. But this means that subsequent playthroughs, where you have to repeat certain steps can become monotonous.

A great piece of music from the game.

Oh! And you can get banned from the junkyard thanks to a random event, which can literally ruin a playthrough since some storylines are dependent upon you crafting items whose components can only be obtained at the junkyard! Or that you can only do one thing per day despite there being four independent characters.

Lastly, eight of the nine endings are really just binary choices. Get to the end of one storyline and you basically are forced to choose between a good and bad ending (sometimes it’s a bad or worse ending). Once I realized this, I was severely disappointed to see that my decisions along a particular story path impacted things so little.

Reading through the bullet points on Steam and the intended goals on the Kickstarter, I couldn’t exactly say that I agreed that the developers met all of their goals. The crafting system that they boast about isn’t exactly compelling. The multiple endings and starting countries were as much a pain in the ass as they were an actual rewarding aspect of the gameplay loop. And I can’t say I was left with the impression that my decisions mattered. (It does, however, probably have the most advanced profanity system of any video game!)

On its surface, that sounds horrible. But bullet points on your storefront and design goals aren’t the same. The devs, above all else, truly want you to empathize with the plight of refugees and immigrants. And after playing Four Horsemen, I can unequivocally say that the quality writing made that a reality for me; and I don’t think I am the only person that will find this game emotionally resonant.

—

[Note: A copy of Four Horsemen was provided by the developer for this review.]

Published: Sep 25, 2017 04:31 am